[Edit 29 October 2021: Due to accessibility requirements I’ve had to remove the colours; sorry about that. – Thomas]

This blogpost is the second and last part about the question of the Indo-European homeland from the perspective of ancient DNA. For the first part – see here, and for an introduction to the traditional methods (before aDNA) of locating the homeland, see here.

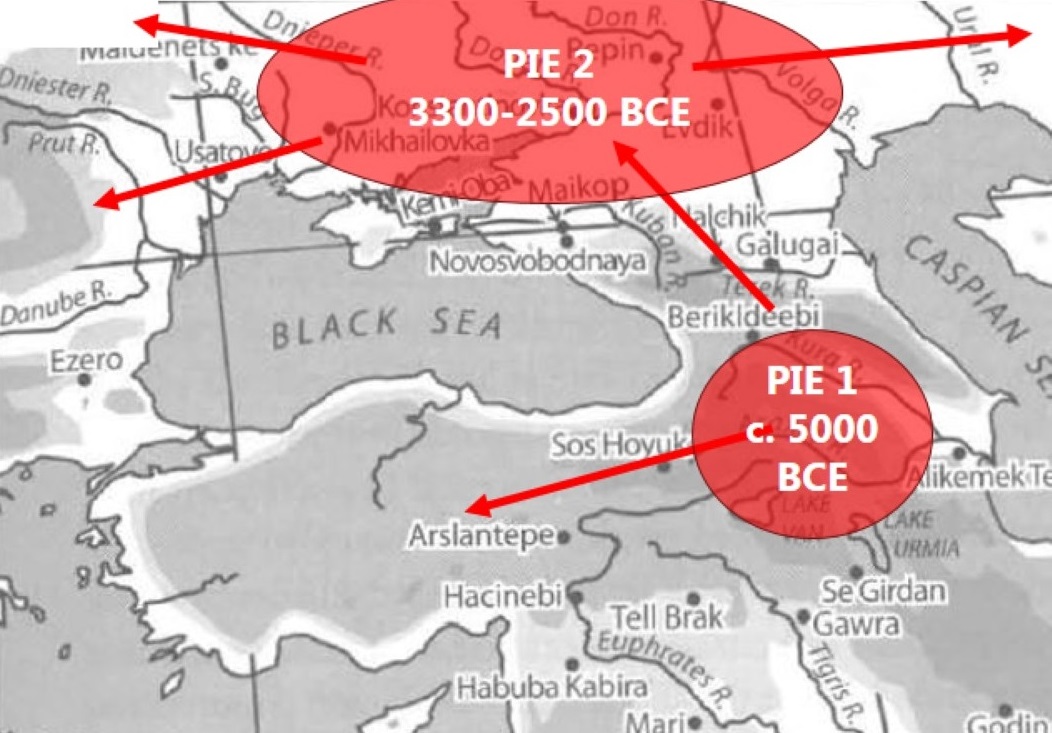

The large share of Caucasian ancestry in the steppes has lead some geneticists to suggest that early Proto-Indo-European (PIE, before Anatolian split off) was perhaps in the South Caucasus until around 5000-4000 BCE, thus splitting west into Anatolia (Anatolian split) while the rest (“core PIE”) went north into the steppes and from there spread east and west with Yamnaya populations around 3000 BCE.

The South Caucasian Homeland model (drawn on a map from Anthony 2007)

While this is not impossible, this South Caucasian PIE homeland model would ignore the proposed close connection between PIE and Uralic (see the blog post about linguistic/archaeological homeland arguments), and the fact that the whole Caucasus region has been occupied by non-Indo-European isolated languages and language families (North Caucasian, Kartvelian, Hurro-Urartian, and Sumerian to the south) for millennia. This leaves quite limited room for a successful language family such as Indo-European to spread and dominate.

The lack of securely reconstructed agricultural terminology is also a problem since the Caucasus region did have agriculture quite early compared to the steppe. Furthermore, a slow 2000 year increase of Caucasian DNA in the steppes, is not a very overwhelming population turnover, and does not speak very much for a language shift. Instead, a hypothesis of Caucasian substrate (“under layer”) influence on the “sound” of PIE could perhaps fit better with a long history of Caucasian females learning to speak PIE in their Steppe husband’s family, influencing their children’s PIE with their own “PIE with Caucasian accent”. This scenario could further be supported by Majkop-like weaving tools (loom weights) and pots appearing in the presumably steppe-related Repin culture sites on the Lower Don river (admitting the assumption that weaving and pottery were primarily done by females). We do, however, also see other Majkop and Novosbodnaya-like tools here such as copper chisels and projectile points which could be more male-oriented.

Cultural and material continuity in the steppes from earlier hunter-gatherer to herder periods has also been argued for, although with different periods of trade links and influence from both the Neolithic Balkan groups and the Neolithic Caucasian groups from 5000-3000 BCE. Furthermore, the Steppe groups still retain a good part of their local Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) ancestry to match this scenario, along with the EHG-related Y-haplogroup R1a, a subgroup of which is spread with steppe-related groups.

So far it seems that when combining linguistics, archaeology and ancient DNA, we can date “core PIE” or “Indo-Tocharian”, depending on which term you like to use (after Anatolian split but before Tocharian split) to around 3400-3000 BCE. When we include Anatolian in PIE (a.k.a. “early PIE“ or “Indo-Hittite”), we might go back to around 4500-4000 BCE. In between, we have a “hiatus” where we do not see any clear expansion from the steppe with the data we have now.

Two very important discoveries can also be added from the many genomic papers that have come out since 2015:

- It seems these Yamnaya people brought an early form of the pneumonic plague (Yersinia pestis) with them as it is found in individuals in the target areas (Central Europe in the west and Altai in the east) of the migrations after 3000 BCE, and also in the North Caucasus around 2800 BCE. We could therefore speculate that one of the important factors in the success of Yamnaya DNA and presumably Indo-European language spread was that some Yamnaya were perhaps more resistant to this plague, and that the locals were not. This scenario would resemble the Europeans coming to America and wiping out the natives with their diseases (and “guns and steel”), which they themselves were immune to.

- The genetic mutation for lactose tolerance that allows adult humans to digest raw milk, especially widespread in modern North Europeans, was not present in Neolithic Europeans before 3000 BCE. It seems to have appeared first in the Pontic-Caspian steppes in a few individuals (first around 4000 BCE in Ukraine), and after they migrated to Central Europe c. 3000 BCE, lactose tolerance very slowly became more widespread over the next c. 1500 years in Europe.

Literature

Allentoft, Morten E., et al. 2015. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522, pp. 167–172.

Anthony, David W. 2007. The horse, the wheel and language: how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bomhard, Allan 2017. The Origins of Proto-Indo-European: The Caucasian Substrate Hypothesis (revised October 2017) (publication unknown). available here

Diamond, Jared 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. US: W.W. Norton & Company

Fu, Qiaomei, et al. The genetic history of Ice Age Europe. Nature 534, pp. 200–205.

Haak, Wolfgang, et al. 2015. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, pp. 207–211.

Jones, Eppie R. et al. 2015. Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians. Nature Communications 6(8912).

Lazaridis, Iosef et al. 2016. Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East. Nature 536, pp. 419–424.

Mathieson, Iain, et al. 2015 Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 528, pp. 499–503.

Mittnik, Alissa, et al. 2018. The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region. Nature Communications 9 (1).

Olalde, Iñigo, et al. 2018. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature 555, pp. 190–196.

Rasmussen, Simon, et al. 2015. Early Divergent Strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 Years Ago. Cell 163, pp. 571–582.

Reich, David 2018. Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Pantheon Books and Oxford University Press.

Valtueña, Aida Andrades, et al. 2017. The Stone Age Plague and Its Persistence in Eurasia. Current Biology 27(23).

Wang, Chuan-Chao, et al. 2018. The genetic prehistory of the Greater Caucasus (preprint). BioRXiv 16 May.